The Snow Cruiser and its crew in Antarctica.

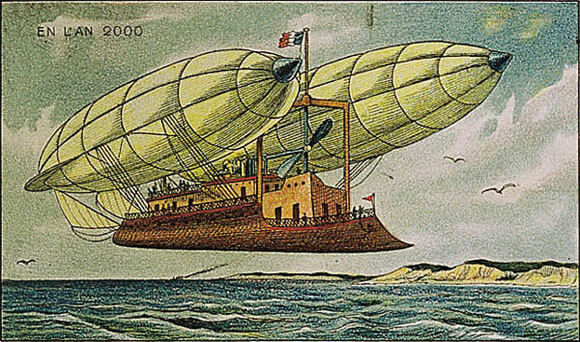

The Victorian Era corresponds well with an age of exploration–exploration of the Poles, as well as Africa and the Far East, not to mention the first ascension of many mountain peaks. And of course, it overlaps with the time frame in which much steampunk literature takes place.

Exploration of the Polar Regions started in the 1800s with the search for the Northwest Passage, and continued into the 20th century. The North Pole was overflown on May 9, 1926 by the American Admiral Richard Byrd in a Fokker Tri-motor plane, although there is some dispute concerning the accuracy and precision of the sextants used and whether the plane could have flown the distance claimed. Nevertheless, a Norwegian expedition commanded by Roald Amundsen reached the pole three days later in the airship Norge cementing the achievement of this goal for good.

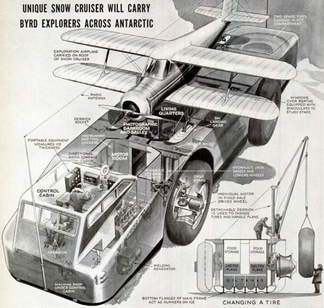

Admiral Byrd commanded several Antarctic expeditions over the decades from the 1930s to the 1950s. On his third expedition, Byrd delivered what he hoped would be an innovative vehicle, the Antarctic Snow Cruiser to the Little America base. The vehicle was designed by Thomas Poulter, a veteran of Byrd’s previous expedition, and was built at the Pullman Company. Its dimensions were huge: 17 meters long and 61 meters wide. During its journey to Boston where it was to be loaded onto the ship to Antarctica, its size caused steering problems, not to mention traffic jams in the cities it passed through.

The Snow Cruiser was designed to extend the range of exploration from the main base of Little America on the Ross Ice Shelf. The Snow Cruiser had living quarters for a crew of five and included sleeping areas, a galley, a machine shop, and a photographic darkroom. More exciting was the biplane that the Cruiser carried to increase its exploration range even further.

When the Snow Cruiser was unloaded from the Coast Gard Cutter North Star at Little America base, problems became evident. The immense weight of the vehicle was such that the ramp from the ship’s deck collapsed. The ten-foot diameter tires were designed to be treadless to prevent encrustation by snow. However, they provided little traction. The tires also sunk into the snow as much as 1-meter deep. Several modifications were tried to improve driving performance, and it was found that driving in reverse increased traction to some extent. However, the Snow Cruiser’s longest trek was only 148 km, accomplished completely in reverse. The biplane did perform some aerial surveys of the area near the Little America base, but not as much as originally expected.

A skeleton crew over-wintered in the Cruiser performing scientific observations. By the next spring, the US government was more concerned with the growing threat of war, and Antarctic exploration was halted. The Cruiser became buried in the snow and eventually the ice shelf where it stood broke away. While it is not known where exactly the Cruiser ended up, it is certain that it now lies on the seabed.

While the Snow Cruiser did not reach its potential, it is still a great example of innovation being harnessed for science, a feature that has continued from the Victorian Age, all the way up to the Apollo moon missions and Ingenuity, the robotic helicopter that just finished its mission flying around on Mars.