One of the more interesting ways to while away the hours is by looking at old photographs, especially those from the birth of photography in the mid-1800s. An amazing amount of detail can be gleaned from a photograph printed from a large glass plate.

But are we really seeing what we think we’re seeing? First off, the images are necessarily monochromatic—black and white. Any color that is seen in black-and-white photographs is a result of hand-tinting the photograph, typically to put some color in the subject’s cheeks. Color photography, although experimented with even early on in photography’s history, was extremely cumbersome, and required laboratory-grade equipment to pull off. Even the great Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell thought about color reproduction and what is considered to be the first color photograph was made using a technique he first described.

So we’re left with black-and-white photography for the Victorian Era. But are we really seeing a proper monochromatic reproduction of reality? In most cases, the answer is no.

First, a bit of chemistry. Most photographic systems rely upon silver—silver halides specifically, silver chloride, silver bromide, silver iodide–as the light-sensitive medium. When light hits a grain of silver halide in photographic film, it causes a chemical change in that grain. To develop the image, the film is treated with a chemical that causes the silver halide to convert to tiny particles of silver metal—the more light that hit the grain of silver halide, the more silver metal is produced. So, something light colored would be translated into a dark blotch of silver particles on the negative. A dark object will show up as few silver particles. Do the process again when you print the photograph from the negative, and the light-colored thing shows up light on the picture.

Or at least this is what we expect (or at least those of us who were around when film still existed expect…) But in early photographic processes, the chemistry was a bit less controlled. The silver halide used was not equally sensitive to all the colors of light. It was very sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum, not very sensitive at all to the red end of the spectrum, and variously sensitive to all the colors in between. It was not until the early twentieth century that panchromatic—meaning “all colors”—films became available.

So this means that blue objects will appear brighter in old photographs, while red and yellow objects will appear darker, as shown in the color chart above photographed with the old type of photographic process.

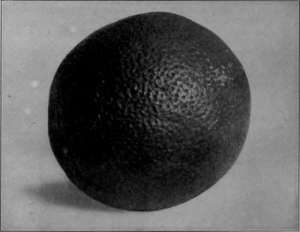

A common example which demonstrates this effect is shown below—an orange sitting on a piece of blue cloth.

Sometimes this effect is noticeable in old photographs, and sometimes not. Blue eyes look kind of creepy, as they appear unnaturally light. This photo of a Confederate flag bearer from the American Civil War might be an example. The blue bars of the flag appear brighter and the red field appears darker. However, there were some regimental flags where the blue and red were switched from the more common Confederate battle flag, and I’m not an expert on the Civil War to know the exact details.

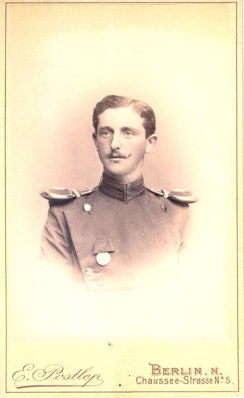

Not surprisingly, those researching period clothing and uniforms are very aware of this problem with old photographs. This photo (below) shows a German officer from the end of the 19th century. The medal with the dark ribbon on his chest is actually yellow! Needless to say faulty color reproduction causes havoc in trying to replicate period uniforms from photographs.

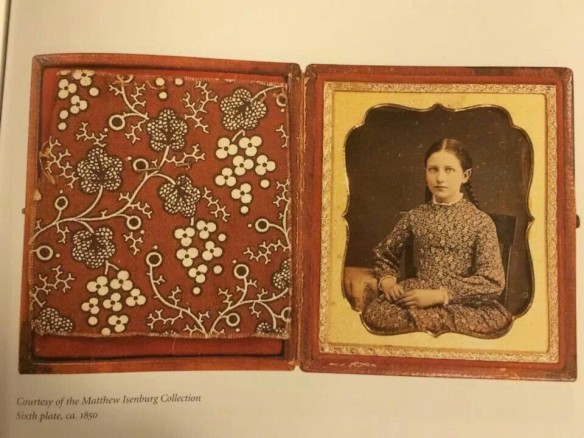

A similar problem exists in identifying dress fashions of the period. Fortunately, sometimes the photograph comes with a color key in the form of a swatch from clothing in the picture. Shown below is one such picture with an accompanying swatch of print fabric with a red background. The effect is not too noticeable here, as the red is fairly dark and the photograph has been extensively tinted.

The next photo shows the effect more dramatically. Looking at the daguerreotype, you’d think the woman was wearing a dark dress with white dots. However, the swatch of fabric pinned to the inside of the case which is clearly the same as the fabric of the dress tells the true story.

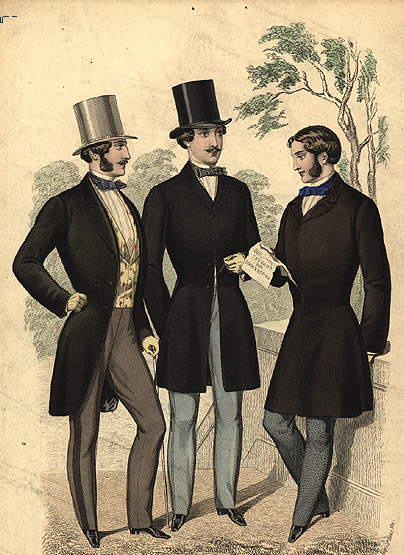

It makes me wonder how many old photographs we have seen with the subjects wearing drab, dark clothing, and assumed that was just how the fashions were in the day, or that the subjects must have been in mourning. How do we know? Well, aside from the very rare case where a swatch of clothing, or the outfit itself, has survived, we must rely upon even older technology: drawing. The periodicals of the day were full of lithographs, showing in glorious full color the latest fashion trends.

Reblogged this on Cogpunk Steamscribe and commented:

This is a thought provoking article about how black and white photography in the Victorian era did not give a true indications of the colours in real life.

LikeLike

From all appearances, the photo of the “Confederate flag bearer” above is actually a modern wet-plate image of a reenactor. Authenticated images of Confederate troops in the field are rarer than hen’s teeth, so an image like this would be a very historically significant find.

Thoughts?

LikeLike

It’s entirely possible that this is a photo of a reenactor. I found this image on Pinterest and unfortunately, it doesn’t lead back to the source. (To their credit, the Pinner did mention that a photo of flag bearers are rare, since they were prime targets.) I can’t find another copy of it by googling. That said, would a modern wet-plate have the same color reproduction issues? Or is this flag not a standard Confederate battle flag?

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I had never heard of this effect before, and it’s certainly thought provoking.

LikeLike

Pingback: My First Blog-iversary | Airship Flamel

Pingback: The Color Guard is Not First | The DrillMaster