During the Victorian Age, when science and technology advanced at a rapid pace, many engineering projects were novel and revolutionary. The Thames Tunnel was one such groundbreaking (pun intended) engineering feat of the Victorian Age, and the one upon which the great Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, cut his teeth.

There had been a need for a tunnel under the Thames River for some time. With increased shipping and docks on both sides of the Thames, a plan was hatched in the early 1800s to dig a tunnel under the river. The Cornish miners put to work on it ran into soft clay and sand deposits, very different than the hard rock they were used to. They managed to dig a pilot tunnel starting on the south bank of the river. It reached 1000 feet in length–almost, but not quite, long enough to reach the north bank, but repeated flooding caused the cancellation of the project.

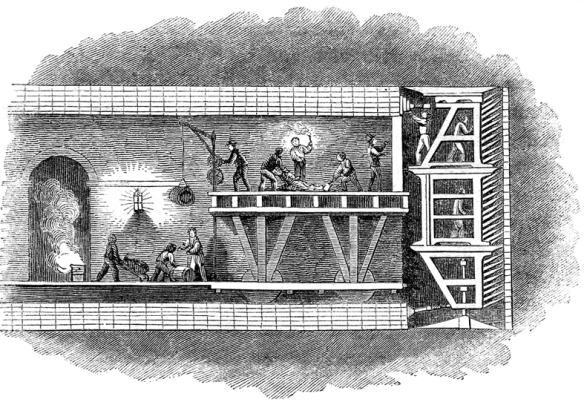

The French engineer Marc Brunel took up the challenge a couple of decades later in 1825. Brunel and his partner had invented a novel method of tunneling: the tunneling shield. This machine consisted of a structure containing 36 frames held against the tunnel face. A miner worked in each frame excavating the earth in front of him. When all the frames were dug out, the entire mechanism was inched forward by screws, and the open tunnel behind the shield was lined with brickwork. Brunel’s shield was innovative, and its legacy was lasting. Similar tunnel boring machines are used today to excavate tunnels, only with rotary cutting tools replacing the miners at the rock face.

Slowly, slowly the tunnel advanced under the Thames at a rate of 10 feet or so a day. The working conditions were horrific. There were floods and cave-ins. Methane gas percolating down from the raw sewage sitting on the riverbed above was periodically ignited by the miners’ lamps, and noxious hydrogen sulfide gas caused the workers to fall ill. (The state of sewage in London at this point in its history is a fascinating topic and I’ll post about it in future.)

When one of the lead engineers fell ill, Brunel appointed his son, just completing his technical education, to replace him. The Thames Tunnel would the be first of many engineering marvels that Isambard Kingdom Brunel would set his hand upon.

The Entrance Hall at the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel. Source: http://www.victorianlondon.org

In January of 1828, the tunnel flooded again. Six workers were killed and Isambard barely escaped with his life only after a workman broke down a locked emergency exit door. The repeated delays caused by the floods caused financial problems, and work was stopped in August 1828. The tunnel was bricked up for seven years.

Eventually, Brunel, bolstered by a loan from the Treasury, raised enough money to re-start the digging. Using a new larger tunneling shield, the excavation was completed, still hampered by additional floods and gas leaks, five years later in November 1841. After the tunnel and its entrances were paved and fitted out with gas lamps, it was opened to the public in March 1843, almost two decades since work started. It was the first tunnel ever constructed under a navigable river.

But, in truth, it was not the tunnel that had been planned. Cost of construction and finishing was over 650,000 pounds, way above its initial budget. Unfortunately cut from the work plan were the ramps at the entrances which would have allowed carriages to reach the tunnel from the surface. So, instead of carrying cargo across the river, the tunnel became a pedestrian way, and largely, a tourist attraction. For one penny, the curious could descend a stairway and walk under London’s great river. Of course, where tourists go, soon follow vendors, selling all manner of items, in the words of one visitor, American author Nathaniel Hawthorne: “multifarious trumpery”. There were musical performers, acrobats, even performing horses (and it’s not quite clear how they got the horses down the staircase.) Over the years, the spectacle became a bit more seedy as muggers and prostitutes began to haunt the darker regions of the tunnel.

The Thames Tunnel as entertainment venue. Source: http://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/

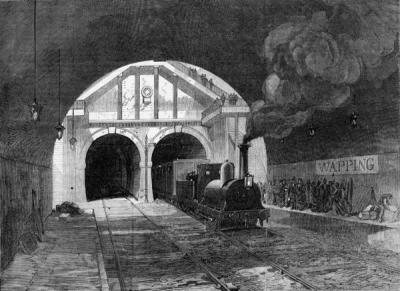

Even though over two million people per year visited the tunnel, it was never financially successful. In 1865, the tunnel was purchased by the East London Railway Company, and it was used for goods trains even after it was incorporated into the London Underground in 1962.

The Tunnel Today. Marc Brunel’s innovative Thames Tunnel still carries London Underground trains today, running between the adjacent stations on the East London Line of Wapping and Rotherhithe on either side of the Thames. During recent renovations on this tube line, there were guided tours of the tunnel. Now, you can only see it as your tube train races through. At the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel, the Brunel Museum occupies the building that once held the steam-driven water pumps used to keep the tunnel dry. The museum is currently fundraising to renovate the Grand Entrance Hall at the original Rotherhithe shaft where visitors descended to the tunnel which should serve as a marvelous monument to audacious Victorian engineering when completed.

Very descriptive blog, I liked that bit. Will there be a part 2?

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this interesting article. More please…this is awesome!

LikeLike

This post was an expanded version of one of the engineers that I talked about in my panel “Building Victoria” at Clockwork Alchemy. I have several more in the works!

LikeLike

Excellent! I’ll be at clockwork next year…looking forward to seeing them!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Airship Flamel and commented:

An update to this blog post of almost two years ago… The Brunel Museum has now completed the renovation of the Grand Entrance Hall of the Thames Tunnel to be used as an event space. See an article describing it here: http://gizmodo.com/london-just-reopened-the-entrance-to-this-underwater-tu-1770977570

LikeLike